Palette

MALIŠA GLIŠIĆ (1886-1916), GREAT, YET FORGOTTEN PAINTER OF EARLY SERBIAN MODERNISM

Fallen Warrior of Art

Although his paintings are exhibited in some of the most important Serbian museums, no one found it convenient to organize at least one solo exhibition to mark a hundred years since his death. It’s the same as if the French completely forgot Claude Monet. He was a Serbian war painter from 1912 till his death. He found his light and the phenomenon of radiating color. He freed the palette and technical procedure, introduced bold coloring, new emotion, tactile value of a painting. He was one of the most vivid Serbian landscape painters and remained joyful in his death. But, did we deserve him?

By: Dejan Đorić

The information that Serbian modernism begins with Nadežda Petrović, which is a general fact of our art history and art criticism, is not correct at all. It’s enough to remember Kosta Miličević, the real forerunner of intimism between the two wars and numerous painters of the faith confessed in this century as well. There is another, even more mysterious predecessor, painter Mališa Glišić (Baćevci, 1886 – Niš, 1916), forgotten by the public and neglected by experts. Those aware of his significance are rare; only the Blue Line of Continuance, history of Serbian twentieth century art, written by art critic Bratislav Ljubišić, begins with Mališa Glišić, which represents boldness and novelty.

The information that Serbian modernism begins with Nadežda Petrović, which is a general fact of our art history and art criticism, is not correct at all. It’s enough to remember Kosta Miličević, the real forerunner of intimism between the two wars and numerous painters of the faith confessed in this century as well. There is another, even more mysterious predecessor, painter Mališa Glišić (Baćevci, 1886 – Niš, 1916), forgotten by the public and neglected by experts. Those aware of his significance are rare; only the Blue Line of Continuance, history of Serbian twentieth century art, written by art critic Bratislav Ljubišić, begins with Mališa Glišić, which represents boldness and novelty.

The time of his appearance, late nineteenth and early twentieth century, is the time of the rise of historical painting, celebrating events and people from national history. The newly formed state, still not entirely liberated Serbian territory from Turkish conquerors, asked for and found national and ideological renaissance in the painting of Paja Jovanović, Uroš Predić, Stevan Todorović and in Vojvodina Stevan Aleksić. Their oleographs decorated Serbian homes at the time. Secession and Ivan Meštrović were the most of contemporariness professor Bogdan Popović, leading aesthetician of European proportions and classical background, could accept.

The time of his appearance, late nineteenth and early twentieth century, is the time of the rise of historical painting, celebrating events and people from national history. The newly formed state, still not entirely liberated Serbian territory from Turkish conquerors, asked for and found national and ideological renaissance in the painting of Paja Jovanović, Uroš Predić, Stevan Todorović and in Vojvodina Stevan Aleksić. Their oleographs decorated Serbian homes at the time. Secession and Ivan Meštrović were the most of contemporariness professor Bogdan Popović, leading aesthetician of European proportions and classical background, could accept.

In such a spiritual climate, the new generation of painters wasn’t accepted well. Kosta Miličević, Mališa Glišić, Nadežda Petrović, Milan Milovanović, Borivoj Stevanović and Moša Pijade found it difficult to introduce their new European experiences into public life, although their painting was not on the barricades of avant-garde at all. While fauvism, cubism, expressionism and abstraction were entering the art scene, they continued the already accepted post-impressionism as a traditional expression.

In such a spiritual climate, the new generation of painters wasn’t accepted well. Kosta Miličević, Mališa Glišić, Nadežda Petrović, Milan Milovanović, Borivoj Stevanović and Moša Pijade found it difficult to introduce their new European experiences into public life, although their painting was not on the barricades of avant-garde at all. While fauvism, cubism, expressionism and abstraction were entering the art scene, they continued the already accepted post-impressionism as a traditional expression.

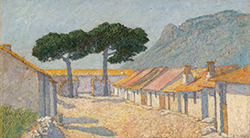

Although he lived only thirty years, Mališa Glišić left an important opus in our environment; his best paintings are remarkable and remembered at first glance. Similar to other painters from that generation, he was a Munich student. The Viennese Academy of Fine Arts, where the previous generation was educated, had already become too conservative.  Impressionism wasn’t so important for him; he found his light and phenomenon of radiating color within a similar aesthetics. He painted in layers and reliefs, abandoning (more than any of his contemporaries) the lazure technique of academic realists. Freeing the palette, he also freed the technical procedure – he used a wide brush, his fingers and the painting knife, despised by certain painters even today. Lazar Trifunović mentions the ”tufted facture”, thick and brutal, which makes Glišić the forefather of informalism. He introduced a completely new sensitivity into Serbian painting, the tactile value of the painting, which is more touched than watched by the eye. Bold coloring with green and yellow light originates from Italy, not Munich and Paris. During his stay and studies in Rome, Glišić discovered the charms of the Mediterranean. It is a question whether his procedure originates from Segantini, as Trifunović believes, since his oils are not so close to the great master.

Impressionism wasn’t so important for him; he found his light and phenomenon of radiating color within a similar aesthetics. He painted in layers and reliefs, abandoning (more than any of his contemporaries) the lazure technique of academic realists. Freeing the palette, he also freed the technical procedure – he used a wide brush, his fingers and the painting knife, despised by certain painters even today. Lazar Trifunović mentions the ”tufted facture”, thick and brutal, which makes Glišić the forefather of informalism. He introduced a completely new sensitivity into Serbian painting, the tactile value of the painting, which is more touched than watched by the eye. Bold coloring with green and yellow light originates from Italy, not Munich and Paris. During his stay and studies in Rome, Glišić discovered the charms of the Mediterranean. It is a question whether his procedure originates from Segantini, as Trifunović believes, since his oils are not so close to the great master.

GHOSTS OF PROVINCIAL CULTURE

The critics at the time did not favor him, and negations enter the area of stupidity. Dimitrije Mitrinović writes about his best paintings as ”technically clumsy” and that ”he has a lot to learn”, Jerolim Miše says that ”he doesn’t have the feeling for distances and depths of the sea and ether of the sky”, as well as that ”his eternally monotonous intonation is tiresome”, Moša Pijade claims that he’s still immature, and Branko Lazararević that he is a dry, airless landscape painter. Such things were written for the most vivid Serbian landscape painter, with the greatest richness of expression. Correctly noticed was only the melancholy in Serbian works: as if the painter expressed his ill fate by painting shells and lonely sharp sea rocks. The Fallen Warrior painting from 1915 is a symbolic presentation of his own self: he passed through life quietly, fell the test of fate, alone in the field of life, without flowers and companions, forgotten by contemporaries and descendants, but joyful even in death.

The critics at the time did not favor him, and negations enter the area of stupidity. Dimitrije Mitrinović writes about his best paintings as ”technically clumsy” and that ”he has a lot to learn”, Jerolim Miše says that ”he doesn’t have the feeling for distances and depths of the sea and ether of the sky”, as well as that ”his eternally monotonous intonation is tiresome”, Moša Pijade claims that he’s still immature, and Branko Lazararević that he is a dry, airless landscape painter. Such things were written for the most vivid Serbian landscape painter, with the greatest richness of expression. Correctly noticed was only the melancholy in Serbian works: as if the painter expressed his ill fate by painting shells and lonely sharp sea rocks. The Fallen Warrior painting from 1915 is a symbolic presentation of his own self: he passed through life quietly, fell the test of fate, alone in the field of life, without flowers and companions, forgotten by contemporaries and descendants, but joyful even in death.

Although his paintings are kept in some of our biggest museums, it’s scandalous that no one found it convenient to organize a single solo exhibition of his works, to mark one hundred years since his death. It’s the same as if the French completely forgot Claude Monet. Incomprehensible laziness and nonchalance of Serbian museum workers was corrected (not for the first time) by Miroslav Rodić, art historian and director of the Belgrade National Gallery, organizing the first posthumous solo exhibition, on the hundredth anniversary of Glišić’s death. The misery of our institutions was again nicely expressed. None of the big museums wanted to borrow the works for the exhibition, so the honor of

Although his paintings are kept in some of our biggest museums, it’s scandalous that no one found it convenient to organize a single solo exhibition of his works, to mark one hundred years since his death. It’s the same as if the French completely forgot Claude Monet. Incomprehensible laziness and nonchalance of Serbian museum workers was corrected (not for the first time) by Miroslav Rodić, art historian and director of the Belgrade National Gallery, organizing the first posthumous solo exhibition, on the hundredth anniversary of Glišić’s death. The misery of our institutions was again nicely expressed. None of the big museums wanted to borrow the works for the exhibition, so the honor of  Serbian art was saved by private collectors. For that occasion, the National Gallery published a voluminous catalogue with a study written by Dragutin Tošić, PhD, one of the best Serbian art historians, who revealed plenty of new information and the correct date of this painter’s death. Until his end, ill fate followed this great man, who other cultures would be proud of; it is sufficient to say that Slovenians don’t have such an artist from that period. We must ask ourselves whether he actually had to be sent to wars, in which he wasted his strength and lost his life.

Serbian art was saved by private collectors. For that occasion, the National Gallery published a voluminous catalogue with a study written by Dragutin Tošić, PhD, one of the best Serbian art historians, who revealed plenty of new information and the correct date of this painter’s death. Until his end, ill fate followed this great man, who other cultures would be proud of; it is sufficient to say that Slovenians don’t have such an artist from that period. We must ask ourselves whether he actually had to be sent to wars, in which he wasted his strength and lost his life.

Mališa Glišić, war painter in all Serbian wars in the early twentieth century, wondrous master of light, coloring and richness of the painted surface, indicates how diverse, unexplored, even neglected, Serbian art is, it’s high worth, which we, incapable of protecting some of our greatest values, are not worthy of and don’t deserve.

***

Life, Paths, Works

Mališa Glišić was born on November 6, 1886 in Baćevci. He graduated from middle school in Belgrade and enrolled in a private painting school in 1903. In 1904, he painted Tašmajdan, his first work, and in 1907 had an exhibition in Belgrade shops. He enrolled in the Academy in Munich in 1908 and started working as production designer in the National Theater in Belgrade the following year. In 1910, he studied at the Academy in Rome, where he participated in the International Exhibition in the Serbian pavilion. His studies were completed in 1912. He was a Serbian war painter in the Balkan wars. In 1914, before the outbreak of war, he had a retrospective exhibition in the Second Male Gymnasium in Belgrade. In World War I, he was a war painter of the Second Army. He died in Niš, in December 1916.

Mališa Glišić was born on November 6, 1886 in Baćevci. He graduated from middle school in Belgrade and enrolled in a private painting school in 1903. In 1904, he painted Tašmajdan, his first work, and in 1907 had an exhibition in Belgrade shops. He enrolled in the Academy in Munich in 1908 and started working as production designer in the National Theater in Belgrade the following year. In 1910, he studied at the Academy in Rome, where he participated in the International Exhibition in the Serbian pavilion. His studies were completed in 1912. He was a Serbian war painter in the Balkan wars. In 1914, before the outbreak of war, he had a retrospective exhibition in the Second Male Gymnasium in Belgrade. In World War I, he was a war painter of the Second Army. He died in Niš, in December 1916.